Transgressive suffering and disembodied minds

Thinking about AI in terms of the ancient docetic heresy

Welcome to AI and Our Faith! This is a monthly newsletter in which I offer my best insights and reflections on the ways in which theological thinking can inform the ethical (dis)use of artificial intelligence (AI). Look out for new releases on the 15th of each month!

In the very early days of the Christian church, even as the New Testament was being compiled, the peculiar notion arose that Jesus did not have an enfleshed, physical body. We find multiple condemnations of this doctrine, which was later given the name of “docetism” (from the Greek verb dokein, “to seem”), in the Johannine letters:

Beloved, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God, for many false prophets have gone out into the world. By this you know the Spirit of God: every spirit that confesses that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is from God, and every spirit that does not confess Jesus is not from God.1

Many deceivers have gone out into the world, those who do not confess that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh; any such person is the deceiver and the antichrist!2

From a present-day perspective, this might seem like an odd debate. The idea that Jesus had a fleshy body seems so obvious that it is simply assumed. In fact, given modernity’s strong emphasis on philosophical naturalism, this idea might be easier to believe than ever. Yet for the proto-orthodox, catholic3 Christians of the early Church, docetism proved to be one of their most formidable doctrinal challenges. For instance, the docetist Marcion of Sinope (who believed, among other things, that the God of the Hebrew Bible was evil and was not the same as the God of Jesus Christ) taught that Jesus simply appeared in the world as a grown adult, without being born. For adherents of docetism like Marcion, Jesus only seemed to be an enfleshed human.

While Marcion might have been the most influential of the docetists (in fact, the first list of canonical books of Scripture was compiled in response to Marcion’s own canon), he was hardly alone in advocating docetic theology. We have copies of several docetic texts, which portray Jesus as something other than an enfleshed human. This made me wonder, why were so many people convinced by a doctrine that seems (to me, at least) to be so counterintuitive? What did they find so appealing about docetism?

In my research, I found that although the term “docetism” derives its significance from intra-Christian debates about Jesus’s nature and identity, docetic ideas are best understood within a broader Greco-Roman cultural context, which supplied a set of expectations about how divine beings should behave. We can identify what these expectations were by looking at quotations from Greco-Roman philosophical critics of early Christianity, which are preserved in Christian apologetic texts. What I’ll demonstrate is that the docetic view of Jesus more closely resembles Greco-Roman cultural expectations of how divine beings should behave than the catholic view does.

Celsus: philosopher, critic, proto-docetist?

One of our literary sources for understanding how non-Christians in the Greco-Roman world viewed Christianity is Against Celsus, an apologetic text by Origen dedicating to refuting Celsus, a Greek philosophical critic of Christianity. Origen quotes extensively from Celsus’s lost polemical treatise, The True Doctrine, allowing us to reconstruct some of his arguments against Christianity. In one peculiar instance, Celsus offers his suggestion of what Jesus “should” have done in order to live up to his divinity:

If he [i.e. Jesus] really was so great he ought, in order to display his divinity, to have disappeared suddenly from the cross.4

The miraculous disappearing act was a common trope in the Greco-Roman world. Another apologetic text, the Apocritus by Macarius Magnes, quotes an anonymous critic of Christianity who unfavorably compares Jesus, who willingly endured his tortures, with Apollonius of Tyana, a philosopher and miracle worker who was said to have publicly defied the emperor Domitian before disappearing from his court.5 These arguments might be best understood in light of Celsus’s presupposition that divine beings do not suffer from their voluntary actions. Regarding the Passion, Celsus wrote,

If these things had been decreed for him and if he was punished in obedience to his Father, it is obvious that since he was a god and acted intentionally, what was done of deliberate purpose was neither painful nor grievous to him.6

Starting from this “obvious” presupposition, Celsus tries to identify a problem with the Agony in the Garden narrative,7 asking,

Why then does he utter loud laments and wailings, and pray that he may avoid the fear of death, saying something like this, “O Father, if this cup could pass by me?”8

We can make Celsus’s implicit argument explicit by reexpressing it as a syllogism:

Divine beings don’t suffer from their voluntary actions.

Jesus did suffer despite expresing a preference not to suffer in his prayer.

Therefore, if Jesus underwent the Passion voluntarily and suffered, he wasn’t divine, because divine beings don’t suffer from their voluntary actions.

But if Jesus underwent the passion involuntarily, he was not divine, because if he was, he would have been able to avoid the Passion. (This explains why Celsus suggested that Jesus should have chosen to disappear from the cross.)

In fact, Celsus appears to have independently developed the docetic view that Jesus only seemed to suffer on the Cross as a “solution” to this supposed contradiction! He thinks that the Crucifixion would have made more sense if Jesus did not really suffer:

You do not even say that he seemed to the impious men to endure these sufferings although he did not really do so; but on the contrary, you admit that he did suffer.9

Docetic accommodation and catholic transgression

We can’t know whether the authors of docetic texts were familiar with Celsus or other critics of Christianity, but Celsus’s arguments demonstrate that docetic texts were composed in a cultural context that found the concept of voluntary divine suffering to be incomprehensible at best and scandalous at worst. By practicing the critical method of “mirror reading,” often used with polemical texts like Paul’s letters, we can analyze docetic texts as part of a broader conversation. In mirror reading, we “use the text as a mirror in which we can see reflected the people and arguments under attack.”10

For instance, this is how the Second Treatise of the Great Seth, a docetic text, describes the Crucifixion:

As for the plan that they devised about me to release their error and their senselessness, I did not succumb to them as they had planned. And I was not afflicted at all. Those who were there punished me, yet I did not die in reality but in appearance, in order that I not be put to shame by them because these are my kinsfolk. I removed the shame from me, and I did not become fainthearted in the face of what happened to me at their hands. I was about to succumb to fear, and I suffered merely according to their sight and thought so that no word might be found to speak about them. For my death, which they think happened, happened to them in their error and blindness, since they nailed their man unto their death.11

The mention of “their man” in the last sentence warrants some explanation. In this text, Jesus switches places with Simon of Cyrene during the Passion, so a possible reading of this passage is that Simon of Cyrene is crucified while Jesus (or at least, the human body that Jesus spiritually hijacked)12 escapes the scene of his punishment.

Why does the author think that crucifying an innocent bystander is somehow a good thing? Notice how the word shame appears twice in this passage—“in order that I not be put to shame,” “I removed the shame from me.” In the Greco-Roman context of the New Testament, the pain and humiliation of the Cross was deeply shameful. But whereas a catholic Christian text like the Epistle to the Phillipians subversively celebrates the Cross as part of Jesus’s exaltation,13 this docetic text accommodates ancient Greco-Roman cultural norms by explaining away the Cross altogether.

Moreover, in this text, the illusory crucifixion serves as post-facto explanation of how Jesus was able to miraculously escape. Remember how Celsus suggested that Jesus should have vanished from the Cross, and how the other critic argued that Jesus should have escaped from his punishment like Apollonius of Tyana? They might have enjoyed seeing how the author of the Second Treatise implemented their suggestions!

In contrast to the accommodationism of the docetists, catholics like Tertullian were willing to attack social mores around honor and shame by embracing the Cross:

What is unworthy of God is needful for me. I am saved, if I am not ashamed of my Lord. He says, “If anyone is ashamed of me, I will also be ashamed of him.” There is no other ground for shame which I can find that will establish me, by my scorn for blushing, as one who is utterly shameless and happily foolish. The Son of God has been crucified; the fact evokes no shame because it is shameful. Furthermore, the Son of God died; the fact can be believed because it makes no sense. Furthermore, he rose from the dead after burial; the fact is certain because it is impossible.14

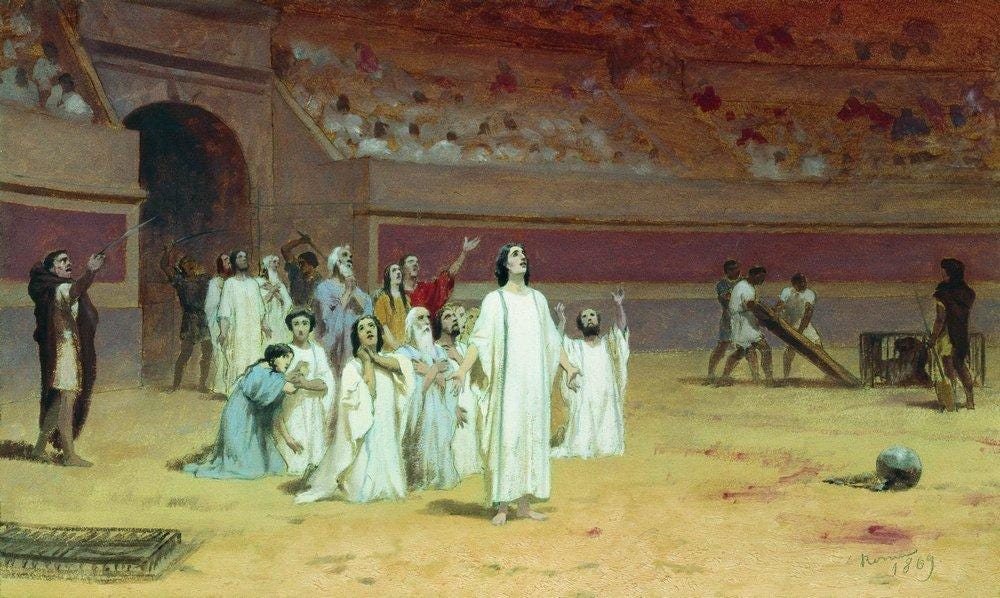

The theological embrace of Christ’s suffering on the Cross was not only a theoretical issue, but it had practical, countercultural consequences. Christian martyrs, believing in the reality of Christ’s suffering, withstood their own trials in light of Christ’s Passion. For example, in The Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity, the martyr Felicity reprimands an abusive prison guard by declaring, “What I suffer now, I suffer; but there will be someone within me who will suffer for me because I will be suffering for him.” Throughout the text, Felicity and her fellow martyrs do not acquiesce to their unjust treatment, but repeatedly find the courage to openly confront Roman legal institutions. For example, when the martyrs are first presented to the public, they threaten the official Hilarianus, declaring, “What you do to us, God will do to you.”15 The willingness to challenge social mores around suffering translated directly into a willingness to challenge the hegemonic power of the Roman imperial system itself!

Transgressive suffering and disembodied minds

Ultimately, the early Church categorically rejected docetism as a heresy, affirming the reality of Jesus’s suffering in public confessions like the Apostles’ Creed:

He suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried.

Although elite philosophical critics like Celsus could not understand how there could be a place for suffering alongside divinity, and docetists like Marcion took the easy way out by accommodating the prevailing theological assumptions of their society, the catholic Christians of the early Church made the radical choice of transgressing Greco-Roman cultural norms by embracing the reality of Christ’s suffering. By recognizing that Christ’s suffering had to be true for Christ’s resurrection to be truly redemptive, the Church affirms that human life in the flesh (as lived by one who was truly God and truly human) is valuable, even in the midst of pain and humiliation.

Today, however, the Church is confronted with an emerging set of cultural norms, which devalue not only the human body, but human life itself. I am referring to what Émile P. Torres has identified as the “TESCREAL bundle,” a nexus of AI-centric, techno-utopian technologies which teach that a utopian society can be built only by posthuman machine minds—tossing aside enfleshed human beings like ourselves! What I find most disturbing is that several TESCREAL ideologists willingly endorse human extinction as a logical consequence of their technocratic schemes:

What can I even say about this? To my surprise I find myself echoing the words of the Eastern Orthodox theologian Brandon Gallaher, “Transhumanism is Satanic”!16

As someone who grew up in a secular, science-oriented, Asian-American household safely removed from the Satanic panics of American evangelicalism, I tend to stop reading once I see the word “Satanic” being tossed around, since I have heard the adjective “Satanic” applied to any number of absurd things, from Dungeons & Dragons to celebrating Halloween. Even as a convert to Christianity, I continue to be skeptical when I see this word tossed around, because I have almost never seen anything being called “Satanic” that even remotely resembles the theological character of Satan!

But Gallaher makes a convincing case that transhumanism (and, by extension, the entire TESCREAL bundle) is genuinely Satanic. Transhumanism, as Gallaher argues, bears the image of the Serpent’s false promise to Adam and Eve in Genesis 3, that they would be “like gods” if they ate from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. For Gallaher, transhumanism is a kind of false self-divinization, an “impatient attempt at seizing our divine inheritance before we are ready for its responsibility. One uses all our intellectual capacities to split open nature, to manipulate its inner parts to serve us as journeymen gods, elevating ourselves, technologically beyond the merely human, and then in a suicidal manner to subsume creation so that all one sees in the cosmos is the idolatrous face of ourselves like Narcissus tipping into the pool.”17 Transhumanism rejects the self-sacrificing love of the embodied Christ, not looking towards the God made human, but towards making the human being a god.

In a few words, Gallaher lays bare the fatal conceits of the transhumanist worldview:

How do transhumanists generally see the cosmos? Mother Nature is something of a disappointment for many transhumanists. There is no sense of the numinous and the holy here, let alone ‘gift’ or ‘sacrament’ as we see in Christianity. […] In short, transhumanism is, like various species of Gnosticism before it, anti-body and anti-creation. It sees corporeality as that force which impedes its upwards trajectory, as transhumanist Simon Young argues: ‘As humanism freed us from the chains of superstition, let transhumanism free us from our biological chains.’18

Just as the early Church radically embraced the human body by rejecting docetism, today’s Church is called to do the same by rejecting AI-centric techno-utopian ideologies. Only when we have set aside the idolatrous exalation of the disembodied mind might we bring about a future in which the human and divine truly meet—“a future that neither scorns technology nor mistakes that power for its Creator.”19

1 John 4:1–3.

2 John 7.

I use “catholic” with a little c, with the sense of “universal,” to refer to the early Christian tradition that was a precursor to Christian orthodoxy, as established by ecumenical councils.

Origen, Contra Celsum, trans. Henry Chadwick (Cambridge University Press, 1980), 2.68, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511555213.

Macarius Magnes, Apocriticus, trans. T. W. Crafer (SPCK, 1919), 52, http://archive.org/details/apocriticusmaca01magngoog.

Origen, Contra Celsum, 2.23.

Matthew 26:36–46.

Origen, Contra Celsum, 2.24.

Origen, Contra Celsum, 2.16.

John M. G. Barclay, “Mirror-Reading a Polemical Letter: Galatians as a Test Case,” Journal for the Study of the New Testament 10, no. 31 (1987): 73–93.

“The Second Treatise of the Great Seth,” in The Gnostic Bible, 1st ed., ed. Willis Barnstone and Marvin W. Meyer, trans. Roger A. Bullard and Joseph A. Gibbons (Shambhala, 2003).

In case you think I’m joking, this is what happened earlier in this text:

I visited a bodily dwelling. I cast out the one who was in it first, and I went in. And the whole multitude of the rulers became troubled. And all the matter of the rulers became troubled. And all the matter of the rulers as well as all the powers born of the earth were shaken when they saw the likeness of the image, since it was mixed. And I was the one who was in the image, not resembling him who was in the body first. For he was an earthly man, but I, I am from above the heavens. I did not refuse them even to become Christ, but I did not reveal myself to them in the love that was coming forth from me. I revealed that I am a stranger to the regions below. —“Second Treatise,” 468.

Philippians 2:4–11.

Tertullian, “On the Flesh of Christ,” in Christological Controversy, trans. Richard A. Norris (Augsburg Fortress, 1980), 61–62.

“The Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity,” in Religions of Late Antiquity in Practice, ed. Richard Valantasis, trans. Maureen A. Tilley (Princeton University Press, 2000), https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv39x560.39.

Brandon Gallaher, “Godmanhood vs Mangodhood: An Eastern Orthodox Response to Transhumanism,” Studies in Christian Ethics 32, no. 2 (2019): 200–215, https://doi.org/10.1177/0953946819827136.

Gallaher, “Godmanhood vs Mangodhood,” 201.

Gallaher, “Godmanhood vs Mangodhood,” 202–203.

Gallaher, “Godmanhood vs Mangodhood,” 215.